In an era of fake news, alternative facts, and conflicting

advice on healthy drinking from even the most reliable sources, it is important

to understand where reporting on clinical science can go awry. Does a glass of

wine before bed help you to lose weight? A widely reported study last year

seemed to suggest just that, at least if you only looked at the headlines. How

about a glass of wine a day is as good as an hour at the gym? Both of these might

be true - if you are a mouse - and substituting resveratrol for wine.

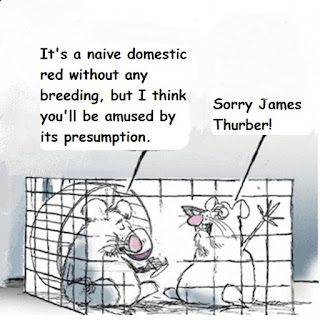

Of mice and men - and medicine

The journey from the research lab to the clinic is known as translational medicine, and the process can be long and unpredictable. Take for example the hypothesis that resveratrol

alters metabolism in a way that mimics exercise (and ignore for the moment the

separate idea that resveratrol supplementation is the same as drinking wine.) There are limits on what sort of

interventional studies you can do to test this idea on humans, before you determine if the doses needed are toxic or have other unexpected effects. Lab rats

make a convenient model for these types of studies, and for trying out

new therapeutic approaches, but they are not people. More than 9 in 10 cancer treatments

that appear promising in animal studies on do not even make it to clinical

trials in humans. Resveratrol supplementation in mice might keep them lean and fit, but it's a huge leap to conclude that wine does the same thing in you and me.

The journey from the research lab to the clinic is known as translational medicine, and the process can be long and unpredictable. Take for example the hypothesis that resveratrol

alters metabolism in a way that mimics exercise (and ignore for the moment the

separate idea that resveratrol supplementation is the same as drinking wine.) There are limits on what sort of

interventional studies you can do to test this idea on humans, before you determine if the doses needed are toxic or have other unexpected effects. Lab rats

make a convenient model for these types of studies, and for trying out

new therapeutic approaches, but they are not people. More than 9 in 10 cancer treatments

that appear promising in animal studies on do not even make it to clinical

trials in humans. Resveratrol supplementation in mice might keep them lean and fit, but it's a huge leap to conclude that wine does the same thing in you and me.

Comments

Post a Comment