It seems that the more studies we see on the relationship

between wine and health, and the larger they are, the more contradictory the

results. Headlines summarizing comprehensive international studies declare the

French paradox dead, and all alcoholic beverages are equally detrimental. I

think there is an overlooked explanation for this: over the past several

decades, convergence of drinking patterns around the world has separated wine

from its role as a daily part of a meal. Globalization has commoditized our

views about drink, toppling it from its role as a culturally specific emblem.

It seems that the more studies we see on the relationship

between wine and health, and the larger they are, the more contradictory the

results. Headlines summarizing comprehensive international studies declare the

French paradox dead, and all alcoholic beverages are equally detrimental. I

think there is an overlooked explanation for this: over the past several

decades, convergence of drinking patterns around the world has separated wine

from its role as a daily part of a meal. Globalization has commoditized our

views about drink, toppling it from its role as a culturally specific emblem.Global convergence of drinking

There are several recent reports summarizing the trend,[i],[ii], [iii]

and it applies for both developed and developing countries. Since the early

1960s, wine’s share of global alcohol consumption has more than halved,

declining from 35% to 15%. Beer and spirits have taken up the slack, with beer

gaining 42% and spirits adding 43%, both large gains. The bigger story however

is convergence; Nordic countries for example have reduced consumption of

distilled spirits in favor of wine and beer, while the ratio of wine versus

beer consumption on a per capita basis in France has fallen from around 6:1 to

less than 2:1. Countries historically favoring beer drink more wine and

vice-versa. Consumers in developing countries are moving their preferences

upscale, while in developed nations traditional practices are discarded as

quaint artifacts. The resulting pattern is not particularly healthful.

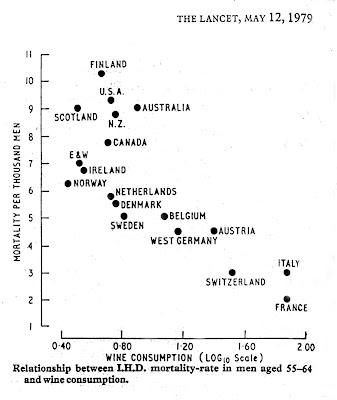

How does this relate to the French paradox and wine’s

privileged position as a healthy drink? Recall that it all came to light when

the French had a strong affiliation with wine and an ingrained pattern of daily

drinking. A now iconic 1979 paper in Lancet[iv]

laid out the case, well before the “French paradox” was even a thing. Comparing

per capita wine consumption by country to mortality from heart disease, a tight

inverse correlation appeared. Italy, France and Switzerland occupied the high

end of wine consumers, enjoying the lowest rates of heart disease, while

countries such as the U.S. were not so big on wine but suffered dramatically

higher rates of heart attack. What’s clear from studies like this and others

that followed is that it is the wine-centric life that makes the difference. It

needs to be almost the exclusive beverage and consumed with regularity. Wine is

still mainly consumed with meals nowadays, but spirits and beer usually not, so

a move away from wine represents a profound shift in how alcohol is consumed.

How does this relate to the French paradox and wine’s

privileged position as a healthy drink? Recall that it all came to light when

the French had a strong affiliation with wine and an ingrained pattern of daily

drinking. A now iconic 1979 paper in Lancet[iv]

laid out the case, well before the “French paradox” was even a thing. Comparing

per capita wine consumption by country to mortality from heart disease, a tight

inverse correlation appeared. Italy, France and Switzerland occupied the high

end of wine consumers, enjoying the lowest rates of heart disease, while

countries such as the U.S. were not so big on wine but suffered dramatically

higher rates of heart attack. What’s clear from studies like this and others

that followed is that it is the wine-centric life that makes the difference. It

needs to be almost the exclusive beverage and consumed with regularity. Wine is

still mainly consumed with meals nowadays, but spirits and beer usually not, so

a move away from wine represents a profound shift in how alcohol is consumed.Why the French paradox is no longer French

The convergence of drinking patterns implies several things

important to epidemiologic research on drinking and health. An important

feature is that populations who consume wine in this strictly traditional way

become difficult to isolate. This could explain much of the disparity between

modern studies and earlier ones, with breast cancer being an enlightening case

in point: Studies generally (but not always) find now that any level of

drinking, of any type, carries some increased risk. But one of the few studies

evaluating breast cancer and alcohol that looked at traditional wine consumers

in a southern French population found a clear J-shaped curve[v].

Comparing several hundred breast cancer cases to matched population controls,

the researchers found that “Women who had an average consumption of less than

1.5 drinks per day had a lower risk when compared with nondrinkers.” They noted

“This protective effect was due substantially to wine consumption since the

proportion of regular wine drinkers is predominant in our study population.

Furthermore, women who consumed between 10 and 12 g/d of wine had a lower risk

when compared with non-wine drinkers.” The odds ratio, a measure of relative

risk, was 0.58 in the light drinking cohort and 0.51 in the moderate drinkers –

half that of nondrinkers.

With wine and health studies, then, bigger is not always

better. Analysis of tens of thousands of people yields limited information when

their drinking habits are not consistent and ritually specific. Researchers try

to get around the issue by categorizing people according to their stated preference of beverage, but convergence

shows that these preferences are increasingly fungible. The French paradox is

alive and well, you’re just more likely to find it at your neighborhood bistro

rather than TGI Friday’s.

[i] Holmes

AJ, Anderson K. Convergence in national alcohol consumption patterns: New

global indicators. Journal of Wine Economics 2017; 12(2): 117–148.

[ii] Bentson

J, Smith V. Structural changes in the consumption of beer, wine and spirits in

OECD countries from 1961 to 2014. Beverages 2018; 4(8).

[iii] Smith

DE, Skalnik JR,"Changing Patterns in the Consumption of Alcoholic

Beverages in Europe and the United States", in E - European Advances in

Consumer Research Volume 2, eds. Flemming Hansen, Provo, UT : Association for

Consumer Research 1995; 343-355.

[iv] St.

Leger AS, Cochrane AL, Moore F. Factors associated with cardiac mortality in

developed countries with particular reference to the consumption of wine.

Lancet 1979 May 12;1017.

[v] Bessaoud

F, Daures JP. Patterns of alcohol (especially wine) consumption and breast

cancer risk: a case-control study among a population in Southern France. Ann Epidemiol.

2008 Jun;18(6):467-75. Case-control study finding lower risk of breast cancer

in moderate wine drinkers.

Comments

Post a Comment